Rochdale Rushbearing

Although Rushbearing might have had its pre-Christian origin in warding off ‘the evil eye,’ official records suggest that in the 7th century, Pope Gregory I urged believers to celebrate ‘wakes’ in remembrance of the saints who kept overnight vigils and to observe the dedication of Christian churches by decorating churches with flowers. Over time, this developed into a feast day with public entertainments including bands, games and funfairs. By the 16th century church bells would ring and the festivities involve the consumption of wine, cakes and ale. 17th century records mention rushbearing and in 1618 James I suggested that women should adorn the churches with rushes.

Eventually there was a practical reason for the strewing of rushes, as church floors – being clay, lime or sand – were extremely cold in winter and so rushes provided warm floor covering throughout the winter months. As this took place in Summer, rushbearing became tied to the ‘wakes’ celebrations, to the harvest and to the end of the growing season – all around the 3rd Sunday in August.

The church warden at St Chads usually dealt with the removal of the old rushes and their replacement with new, often spreading them in the churchyard to dry before strewing. Putting rushes on the church floors was not, however, without its problems as they tended to become louse-ridden and records suggest that some children in the 17th century were paid pennies to bring hedgehogs into church to eat the infesting insects.

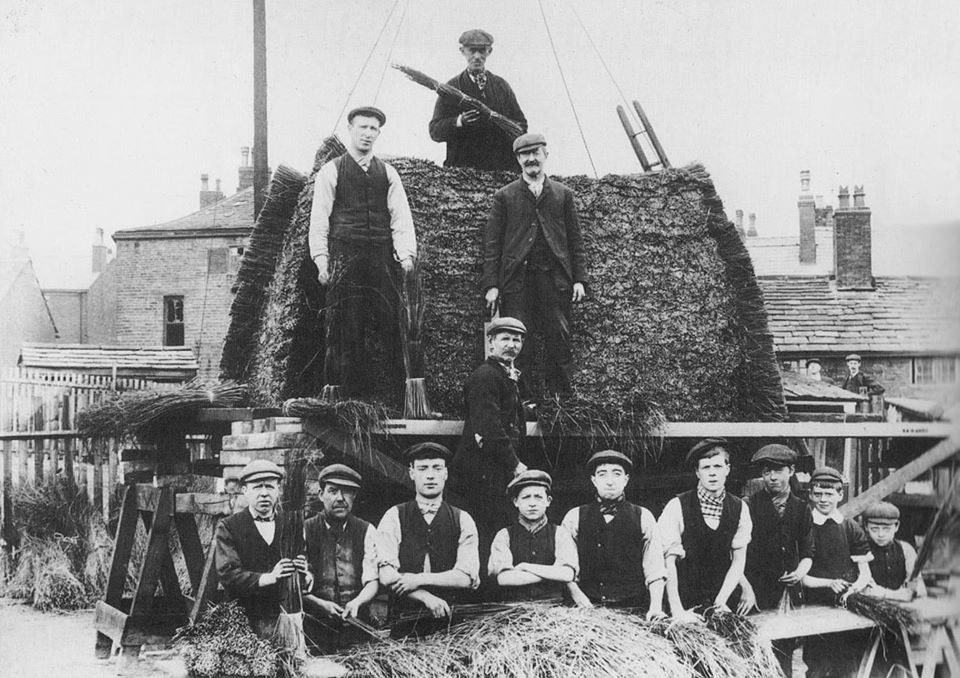

shes themselves, collected and trimmed by young men of a village, were built up to the height of 12 feet often in a cone shape with a ‘crown’ or bower at the top. There were some variations, however, the Whitworth ‘stack’ of 1910 for example being rectangular with windows. Building the rushes was a little like thatching, a skill that could demand a fee of 10 shilling in 1878. On the front of the rushes was a sheet decorated not only with flowers, twigs and fruits but sometimes with silverware such as spoons and tea pots. The carts – borrowed from farms or from factories – were often painted and would be hung with garlands of flowers which were later used to decorate the church. The procession was accompanied by Morris teams, children carrying flowers and musicians. On top of the central rushcart, high above the road, sat the ‘Chairman’ who was either a young boy or, more likely, a local well-known character who, when he wasn’t being covered in flowers thrown from the crowds, would be lowering a cup on a string to fill up with beer. Middleton had ‘Owd Stiff’ as their chairman whilst the well-known Rochdale chairman was ‘Little Joss’ a tiny, disabled man known throughout the town.

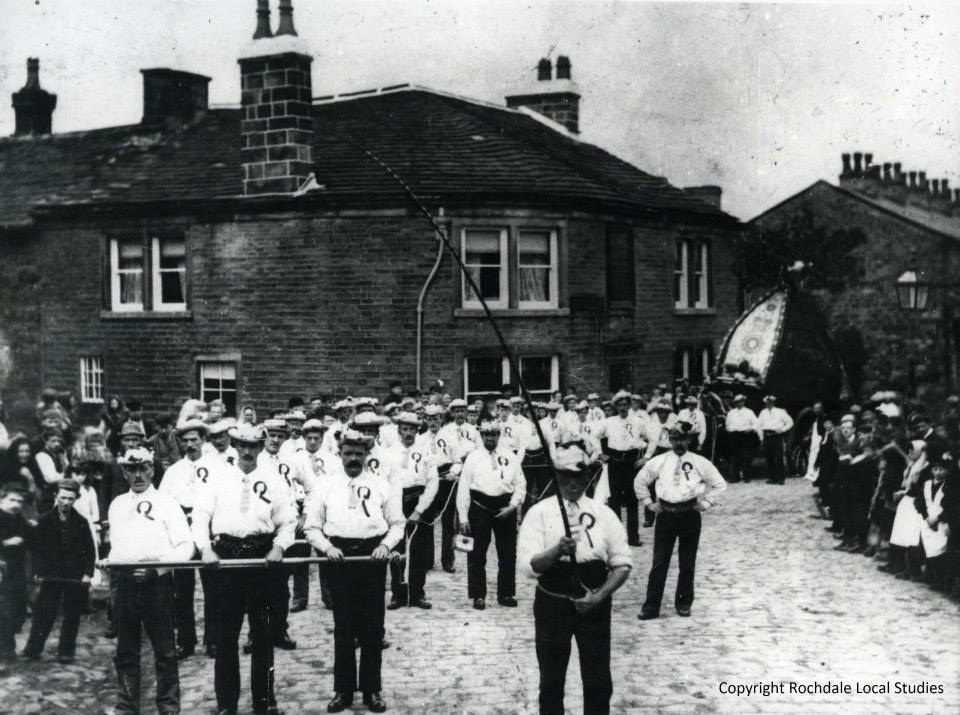

The Rochdale rushcarts – drawn from many villages nearby – were normally assembled near to The Butts with the line preparing to process, stretching up Yorkshire Street. The procession was often preceded by Morris Men followed by girls carrying garlands representing ‘Peace and Plenty.’ After that would come banners made of silk and other materials decorated with ‘treasures’ to represent clubs and industries. The rushcart following was pulled by two lines of garlanded men yoked in ‘stangs’ which were towing poles held by the pairs of men and raised and dropped in time to the music. Accompanying the procession were ‘whifflers’ carrying horse whips which they cracked to clear the way and to encourage coins to be thrown into a sheet, the money to be donated – in one year – to Rochdale Infirmary.

There was much rivalry between villages, at least 8 carts converging on the town centre for the procession in any year. In the 19th century the ‘Marland lads’ were reputed to have had an excellent rushcart.

Records show that in 1827 20,000 people came to Rochdale town centre to watch the processions amid accompanying drinking and revelry which sometimes led to arguments and fights between rival village cart teams. This raised inevitable complaints and claims about the decline in morality in 19th century England. Rochdale rushbearing festivities reached their height around 1850 but by the time of the Great War were dying out. A number of revivals through the 1980’s and 1990’s have rekindled the old Rushbearing flame, however, and an annual festival held to this day in Littleborough.