Turnpikes in Rochdale

Under a General Statute of 1555 people who lived in a particular manor in England were obliged to look after the pathways and roads within their boundaries and could incur a fine if they didn’t. This meant mending the roads themselves. Rochdale, as any other town, had to conform to this and records exist of a summons in 1639 for James Milne and John Howarth for ‘not working on the highroad in Spotland.’ However because the system was inefficient and the roads between towns falling into disrepair to the extent that some became impassable, in 1706 the Turnpike Act gave the opportunity for speculators instead of citizens to build and maintain roads and charge those using them. Every year, Parliament would set up bodies consisting of named persons empowered for 21 years to look over a stretch of road and charge a levy. This would solve the problem of poor roads.

However, these ‘turnpike’ trusts were slow to be set up such that an indictment was laid against the old township of Hundersfield east of the town ‘for not repairing Rachdale streets’ as late as 1738. Other local roads however, possibly because they were trade routes, were turnpiked. For example the road over Blackstone Edge was turnpiked in 1735 due to its difficulty in transporting goods, it being too narrow in places, had poor soil surfaces and was ‘a land of breakneck’ in Winter. The 1730’s therefore became a decade for much road building and maintenance.

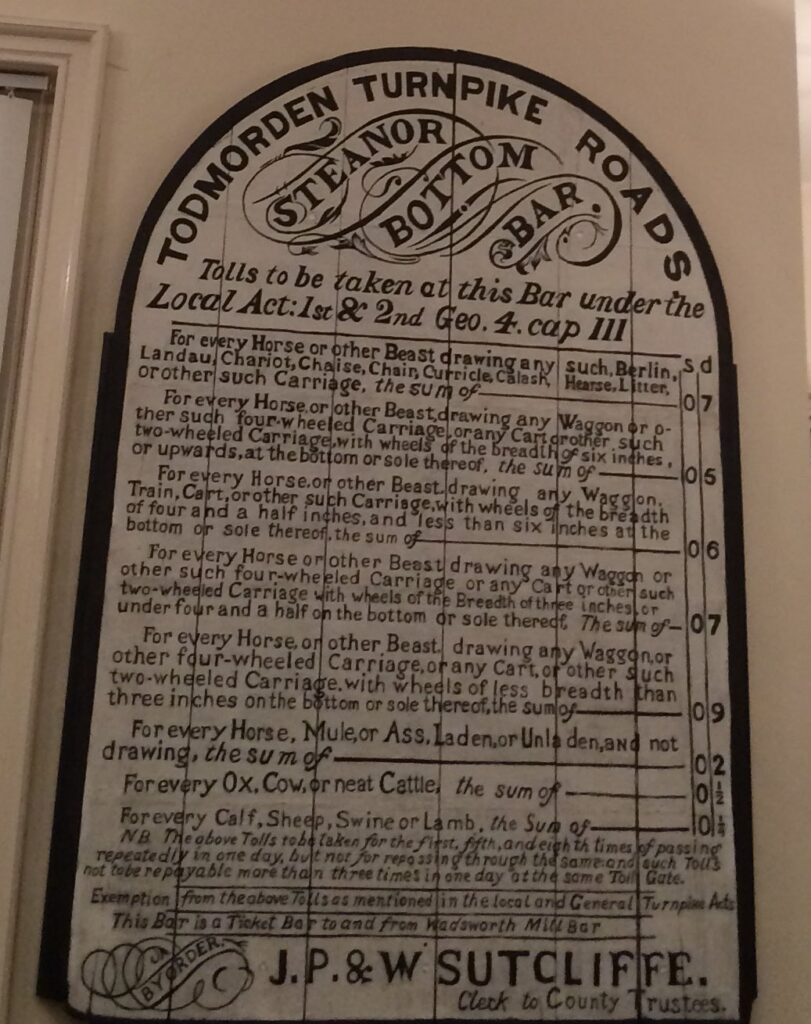

The administration and running of the turnpike trusts was in the hands of a few men who would meet regularly, the clergy often being active as members. The fee for tolls varied a great deal although the Turnpike Act suggested that a coach with 6 horses had to pay 2s (10p), a hearse 1/6 (7.5p). Generally, that the charge depended on the number of wheels, the size of the wheel and the number of horses. The moving of livestock through the toll gate was charged depending on the number of animals although exemptions did apply for local farm transport, unladen horses and people travelling to church.

In Rochdale the development and implementation of turnpikes took hold from the 1750’s with one set up at the top of Toad Lane, one on Spotland Bridge, one on Manchester Road and a toll bar on the road to Burnley in 1755. Others, in time, came along with turnpikes to Todmorden over Calderbrook (1758), to Bamford and Bury (1797), at Norden where Clay Lane joins Edenfield Road (1797), to Shaw (1805) to Newhey for Huddersfield (1806) and to Royton (1825) amongst others. The results of such charges were not immediately apparent with little highway improvement being made although there was, for example, road widening in Toad Lane, in Heights Lane and at Healey Hall and traffic as a result increased on these and other thoroughfares. For example, in 1772 there was a regular coach service between Manchester and Leeds but by 1821 there were 6 coaches a day between Rochdale and Halifax, additional horses having to be coupled in Littleborough for the trail over Blackstone Edge.

But not all results were good. Road repairs were often poor because flattening the surface, as many did, allowed standing water to stagnate whilst other repairs sloped the road to a camber that threw vehicles into roadside ditches. Some travellers used circuitous routes to avoid toll bars, others un-yoked their horses and led them down alternative routes.

By 1820 turnpikes covered only 1 in 6 of the country’s highways, the rest remaining under parish control so by the 1840’s apart from 6 or 7 major roads, Rochdale streets were still maintained by the hamlet or the parish. However, 1,100 turnpikes existed by then across the country administering 23,000 miles of road with 8000 toll gates and this meant that there was an unruly patchwork of road maintenance across England alongside some accusation of gatekeepers over-charging and poorly regulated trusts or trusts being sold at extortionate fixed prices to the highest bidder.

A number of things led to the demise of the turnpikes. The rise of the railway in the 1830’s meant that roads were used less frequently for transporting goods and so investment passed from one to the other. As a result, some turnpike trusts wishing to continue had to borrow money from banks at high interest rates. Roads became impossible to keep in a good state and there arose, across the country in the 1860’s, public agitation about the continued charging, the best known demonstration being the Rebecca Riots where toll bars were physically destroyed. In 1872 the Rochdale Improvement Act abolished the town’s turnpikes, the last to go being between Milnrow and Shaw.

Today we pay road tax, but drivers cursing the ravages that potholes have on their cars may well look back on the days of the turnpikes and before and reflect that an effective way of maintaining our roads has yet to be found.