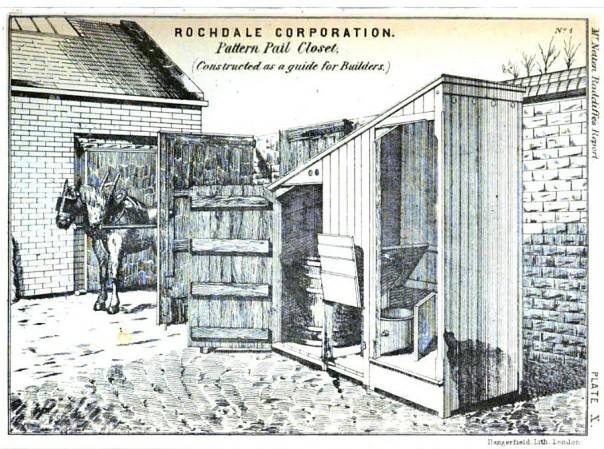

The Pail Closet

Rochdale is famous for many things, for Gracie Fields and for the Rochdale Pioneers to name only

two. However, it is with a less attractive but nonetheless necessary domestic institution that

Rochdale gave its name, the Pail closet, also known as the ‘Rochdale system’.

There were a number of ways in which human waste was disposed of in the 19 th century including

the dry earth system and the midden or privy midden. By the 1860’s Manchester had 10,000 flush

toilets but more than 38,000 middens which were sometimes no more than a hole in the ground, a

dunghill or an ash pit. Sometimes called Lancashire middens, they held particular dangers to the

public. Not only did they overflow and cause river pollution but they were one of the main reasons

typhoid became a killer in society, particularly amongst the working class. Developments such as

ventilation shafts and deodorising mixtures made middens a little more hygienic and less of an

immediate danger to public health but they were difficult to empty and clean so an alternative was

sought.

Wealthier homes had flush toilets (usually outside the house) but the lack of effective water supply

meant that for many working people in heavily built-up areas waste had to be dealt with as it was or

‘by dry conservancy’. Rochdale Corporation looked at the French Goux system which was used in

Halifax whereby waste materials were absorbed by straw, grass or cotton mixed with a chemical

compound which broke it down before land disposal or conversion into compost. Instead, in 1869

Rochdale chose the Pail Closet system which was created in 1868 by Edward Taylor, a local

pharmacist with a shop on Yorkshire Street who had a sense of urgency about the health

consequences of poor water supply and the disposal of waste in the town. Furthermore, he had

advanced ideas on how to turn human waste to profit. In his system, an outside toilet or closet

contained a seat under which stood a wooden 10 gallon pail or bucket at the bottom of which would

be left one sixteenth of an inch of disinfectant or ashes. An air-tight lid on the bucket made for ease

of removal. According to records in 1871 the full pails were removed once a week.

By April of 1869 100 pail closets had been set up in Rochdale. The waste, sometimes known as ‘night

soil,’ was mixed with half a pint of antiseptic fluid then taken away under the auspices of the

Scavenging Department on a 24-bay wagon to a building near the railway station but later to a depot

on Entwistle Road which became known as the Manure Works. A replacement pail was left behind in

the closet. By 1874 Rochdale had five of these wagons collecting over 3000 buckets on a weekly

basis across the town and by 1876 this number had grown to 5000 serving over 300 closets.

On reaching the depot the wagons would empty the night soil into storage tanks whilst the pails

were washed and chlorinated. The dried waste was then either burnt or developed – with the

addition of fine ash – into fertilizer which was sold to local farmers at £6 10 shillings a ton. This early

process of re-cycling of human excrement for agricultural purposes had been discussed for decades

but never implemented. Records show that 9000 tons of waste was removed from the toilets of

Rochdale each year and whilst every effort was to make the system as hygienic as possible, Rochdale

people often complained about the smells, especially in difficult winter conditions when the wagons

couldn’t always get round.

Whilst we, with our modern drainage systems and our water supplies might blanche at such

primitive systems, the Rochdale Pail system was an improvement on the middens and must have

seemed quite hygienic compared with what had gone before. Opinions differed as to the

effectiveness of the Rochdale system, Henry Roberts in 1873 writing that it failed the first sanitary

laws in that it distributed rather than confined the smells. Others such as J R Heape, Rochdale’s

Mayor in 1888, commented that the system had brought ‘comfort and health to the town.’

Gradually Rochdale’s drains and water supplies were improved and by the beginning of the 20 th

century the Pail system or the Rochdale System was replaced by the water closet and flushing

mechanisms. The Rochdale system is, however, still used in some parts of the world, notably in

Australia where the ‘dunny’ has achieved something of comic celebrity.

Although Rochdale was visited by many from around the globe in the 19 th century to evaluate the

system’s effectiveness, it was not taken up universally possibly because of its substantial cost to

small towns. Larger towns, however, such as Wakefield, Salford, Leeds and Huddersfield did take on

the Rochdale system and whilst it had its faults and dangers to public health it was a step on the way

to transforming the handling of human waste to the system we know today.