The Dialect Monument 4 : Oliver Ormerod

The art of dialect writing looks to celebrate the local sounds, lexicon and construction alive in the

spoken language of a particular place. Lancashire dialect has its own idiosyncrasies, especially its

flattened vowels and shortened words but it’s important to note that there are further aural

distinctions that can be made when looking at dialects from individual towns. Oldham and

Manchester dialects differ from those from Blackburn and Burnley and Rochdale has its own ‘voice,’

a voice which is particularly admired in the history of dialect literature. The celebration of it is

commemorated in two places in Rochdale. Obviously, there is the resting place of John Collier,

better known as Tim Bobbin, in the graveyard of St Chad’s Church and as a dialect writer he was

important in capturing the voice of the people, especially the working people of the town. Tim

Bobbin was a rather eccentric but powerful dialect model, but he was followed by four Rochdale

dialect writers in the nineteenth century who made their mark. These four dialect writers are

commemorated by a monument in Broadfield Park which serves to remember the works of Edwin

Waugh (see Streetwise January 2020), Margaret Lahee (see Streetwise February 2022), John Trafford

Clegg (see Streetwise May 2021) and the subject of this article, Oliver Ormerod.

Oliver Ormerod was born in 1811 and in mid-life became an honoured and worthy member of the

town’s cultural society, being a prominent contributor to the Rochdale Literary and Philosophical

Society and taking part in the radical politics of the town. These interests are clear in his writing,

especially in his rather satirical take on the establishment.

Writing from an early age, Ormerod came to prominence when he wrote and published a prose

account concerning The Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in London. This dialect piece was

more than simple journalism as it caught through dialect what a northern man might feel about an

event taking place far away in the capital. These recollections of his visit to the exhibition were

published by Dr Henry Colley March who was also a surgeon at Rochdale Infirmary and one of the

founders of the Rochdale Literary and Scientific Society. In his writing, Ormerod expressed a wish to

hone his ‘native handiwork’ and try to capture his recollections, not simply in the northern dialect

but in a dialect particular to Rochdale. He did this in his book of 1851 entitled O Ful, Tru, un Pertikler

Okeaawnt o bwoth wat aw seed un wat aw yerd, we gooin too Th’ Greyt Eggshibishun, e Lundun, an

a greyt deyle of Hinfurmashun besoide. In a modern ‘translation’ this would be ‘A full, true, and

particular account of both what I saw and heard when going to the Great Exhibition, and London,

and a great deal of information besides.’ Even from the title it is easy to see the comic and rather

satirical side of Ormerod’s writing, characteristics of which Tim Bobbin would have approved.

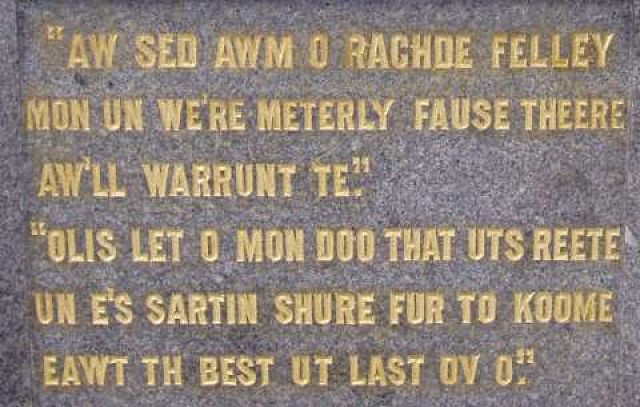

Later, in 1856 Ormerod published further personal accounts of being a Rochdalian in his book

‘Rachde Felley’ which ran to a number of editions and sold well nationally. His avowed intent was to

show to a wider audience the rich tones and the local vocabulary that existed in the town’s dialect

but also to do this with a sense of Rochdale comedy. We can see the local wit of Ormerod in the

following passage about his visit to the Great Exhibition (I would love you to try to read the dialect

version out loud before looking at the ‘translation’) :

“Wel, us aw wor gooin hinto won uth reawms, whoo shud aw see but Sam o’Jacks fro Owdum. E wor

us gloppent up seein me us aw wor ut seein im. Sam’s o reglur rufyed, fur they koen Owdum foke

rufyeds oppo sum keawnt, aw dunnut eggsaktly kno wat fur but ony buddi e Rachde knone us it is

so.”

In translation this would be :

‘Well, as we were going into one of the [Great Exhibition] rooms, who should I see but Sam O’Jacks

from Oldham. He was as stunned to see me as I were at seeing him. Sam is a regular rough head, for

they call Oldham folk rough heads upon some count, I don’t exactly know what for but anybody in

Rochdale knows that it is so.’

Ormerod’s expressions and renditions of the language of folk from the town are notable for having

been written with good humour and sensitivity. They certainly don’t look down on ordinary people

and in fact serve to value the language and culture of ordinary Rochdale people. Not known as

widely as Edwin Waugh nor as culturally significant as Margaret Lahee, nonetheless Oliver Ormerod

earned his place on the Broadfield Park memorial and his dialect writing still captures a poetic

vernacular which is rich in local history and which identifies Rochdale as ‘home’ in a distinctive

literary way.