Pace Egging in Rochdale

As long ago as the 16th century pageants featuring St George were performed in the streets of England. Thomas Hardy in ‘The Return of the Native’ described a battle between St George and a Turkish knight and doctors plying their trade in miracle plays were well known in the 15th century. The West Country had versions of a Mummers Play with fixed characters although it has been suggested that the Pace Egg has roots in Northern Sword Dance rituals. Others claim that Mummers Plays originated in fertility rites or the ritual of a pagan ‘waking of Winter from sleep’ although few, if any, records exist to support its existence before medieval times. Rather, Mummers Plays began between 1700 and 1750. In the 19th century what were known as Raper Dancers featured eight boys performing a Mummers Play in Brighouse on Easter Monday, setting Easter as the time for Pace Egging in the North of England. Although once witnessed throughout England, its most recent manifestations have been in Lancashire and West Yorkshire, especially in Rochdale.

What had been once an exclusively male and adult tradition was passed in the 19th century to children and young people to carry it forward and in Rochdale, Pace Egging became an important part of the Easter celebrations with young boys from the same streets, neighbourhood or from a school seeing it as an opportunity to act out a traditional play and make money besides.

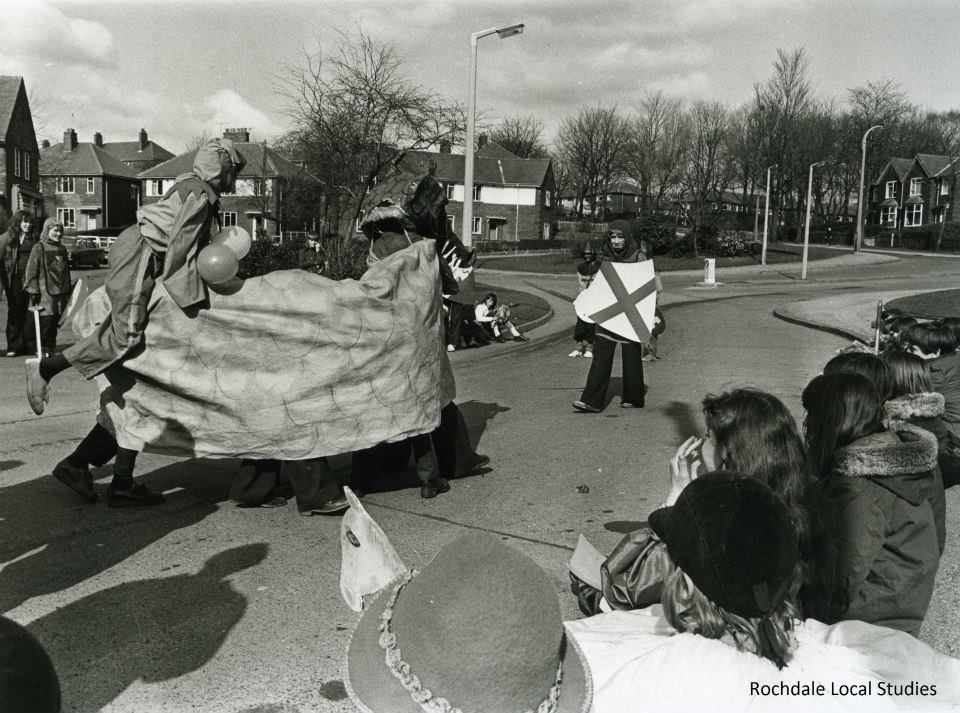

Many of the plays which constituted the Pace Egg were not written down but passed on through families and generations of friends. There were, however, common features. A sweeper would enter first to make a circle for the play and then characters would enter one by one telling the tale of mock battles, death and revival. St George would take on such characters as (bold) Slasher, the Prince of Paradine and the King of Egypt whilst comic interruptions would come in different versions from the Fool, Beelzebub, Dirty Bet or Toss Pot. A hobby horse and a dragon featured in the early Rochdale plays and in some versions (certainly the one at Moorhouse School Milnrow in the 1950’s) patron saints of the British Isles would feature and fight. The main characters however were St George, enemy knights, a Doctor with a top hat and long frock coat carrying a bag with his medicines, and Dirty Bet sometimes played by the most timid boy dressed up as a woman with a bonnet and a basket to collect money or – sometimes – eggs from the audience. Dirty Bet, a Rochdale alternative to Beelzebub, Devil Doubt or Toss Pot, would conclude the performance with a collection rhyme or song about kissing the girls before a final circle-dance drew together the whole cast.

In some versions a character called Devil Doubt would threaten the audience with his broom if they didn’t give money and it is true that one key purpose of the local plays was to make a collection, money being scarce and every copper helping some families in times of need !

In Rochdale the play was performed by young lads in the streets of many parts of town. There were ‘Street teams’ from Milnrow, Whitworth Road and Lower Place which played locally but also in the 1940’s a Pace Egg took place on the town’s Cattle Market where the Police Station now stands. Local schools, scout groups, Sunday Schools may all have had their own Pace Egg, some choosing to perform in more wealthy areas of the town so that they could get a better ‘pay day.’

Costumes consisted of home-made regalia with breastplates and helmets. Sometimes the boys wore cloth smocks decorated with sashes or covered in ribbons, bits of cloth or strips of paper. The knights would carry swords made either of wood or actual iron which were sold for 1d and 2d each depending on the size (along with the scripts) from the printers Edwards and Brynings. In some parts of the country the performers’ faces would be blackened and this was certainly the case with the early Rochdale plays.

Not everyone enjoyed a Pace Egg play. One report from 1914 recounted by Hutton in his book ‘Stations of the Sun’ said that the performances in some towns had ‘dinned the long-suffering householders into a state of mental distress’ and that they had to stop !

Over the years and particularly since the 1950’s, interest and enthusiasm for the Pace Egg has waned, only one last special printing of the play’s script or chapbook being made in the 1960’s. And such a ritual’s decline is not without precedence as similar childhood games – marbles, peggy, whip and top – and rituals such as Mischief Night and April Fool’s Day fail these days to gather the enthusiasm they once had. This is not surprising. Television, computer games, the rise of the individual citizen in preference to community activities, all such elements of ‘progress’ have contributed to such a demise.

All the more credit, therefore, to those locally who still perform the play. Rochdale’s Curtain Theatre have recently put on performances, Middleton has a Pace Egg group and there are traditional Pace Egg plays in the Calder Valley’s Todmorden, Hebden Bridge and Heptonstall on Good Friday every year. Long may they continue !